Encoding and Evolution

Introduction

Applications inevitably change over time. Features are added or modified as new products are launched, user requirements become better understood, or business circumstances change. In most cases, a change to an application’s features also requires a change to data that it stores: perhaps a new field or record type needs to be captured, or perhaps existing data needs to be presented in a new way.

When a data format or schema changes, a corresponding change to application code often needs to happen (for example, you add a new field to a record, and the application code starts reading and writing that field). However, in a large application, code changes often cannot happen instantaneously:

-

With server-side applications you may want to perform a rolling upgrade (also known as a staged rollout), deploying the new version to a few nodes at a time, checking whether the new version is running smoothly, and gradually working your way through all the nodes. This allows new versions to be deployed without service downtime, and thus encourages more frequent releases and better evolvability.

-

With client-side applications you're at the mercy of the user, who may not install the update for some time. This is particularly present in mobile development. Users oftentimes do not update mobile applications, and do not have automatic updates enabled.

Formats for Encoding Data

Programs usually work with data in (at least) two different representations:

-

In memory, data is kept in objects, structs, lists, arrays, hash tables, trees, and so on. These data structures are optimized for efficient access and manipulation by the CPU (typically using pointers).

-

When you want to write data to a file or send it over the network, you have to encode it as some kind of self-contained sequence of bytes (for example, a JSON document).

Thus, we need some kind of translation between the two representations. The translation from the in-memory representation to a byte sequence is called encoding (also known as serialization or marshalling), and the reverse is called decoding (parsing, deserialization, unmarshalling).

Language-Specific Formats

Many programming languages come with built-in support for encoding in-memory objects into byte sequences.

These encoding libraries are very convenient, because they allow in-memory objects to be saved and restored with minimal additional code. However, they also have a number of deep problems:

-

The encoding is often tied to a particular programming language, and reading the data in another language is very difficult. If you store or transmit data in such an encoding, you are committing yourself to your current programming language for potentially a very long time, and precluding integrating your systems with those of other organizations, which may use different languages.

-

In order to restore data in the same object types, the decoding process needs to be able to instantiate arbitrary classes. This is frequently a source of security problems: if an attacker can get your application to decode an arbitrary byte sequence, they can instantiate arbitrary classes, which in turn often allows them to do terrible things such as remotely executing arbitrary code.

-

Versioning data is often an afterthought in these libraries: as they are intended for quick and easy encoding of data, they often neglect the inconvenient problems of forward and backward compatibility.

-

Efficiency (CPU time taken to encode or decode, and the size of the encoded structure) is also often an afterthought. For example, Java's built-in serialization is notorious for its bad performance and bloated encoding.

For these reasons it's generally a bad idea to use your language's built-in encoding for anything other than very transient purposes.

JSON, XML, and Binary Variants

Moving to standardized encodings that can be written and read by many programming languages, JSON and XML are the obvious contenders.

There is a lot of ambiguity around the encoding of numbers. In XML and CSV, you cannot distinguish between a number and a string that happens to consist of digits (except by referring to an external schema). JSON distinguishes strings and numbers, but it doesn't distinguish integers and floating-point numbers, and it doesn't specify a precision.

JSON and XML have good support for Unicode character strings (i.e., human-readable text), but they don't support binary strings (sequences of bytes without a character encoding). Binary strings are a useful feature, so people get around this limitation by encoding the binary data as text using Base64. The schema is then used to indicate that the value should be interpreted as Base64-encoded.

Despite these flaws, JSON, XML, and CSV are good enough for many purposes. It's likely that they will remain popular, especially as data interchange formats.

In these situations, as long as people agree on what the format is, it often doesn't matter how pretty or efficient the format is. The difficulty of getting different organizations to agree on anything outweighs most other concerns.

Binary encoding

For data that is used only internally within your organization, there is less pressure to use a lowest-common-denominator encoding format. For example, you could choose a format that is more compact or faster to parse. For a small dataset, the gains are negligible, but once you get into the terabytes, the choice of data format can have a big impact.

Thrift and Protocol Buffers

Apache Thrift and Protocol Buffers (protobuf) are binary encoding libraries that are based on the same principle. Protocol Buffers was originally developed at Google, Thrift was originally developed at Facebook, and both are now open source.

Both Thrift and Protocol Buffers require a schema for any data that is encoded.

Thrift and Protocol Buffers each come with a code generation tool that takes a schema definition like the ones shown here, and produces classes that implement the schema in various programming languages. Your application code can call this generated code to encode or decode records of the schema.

Note that there are no field names in the schema. Instead, the encoded data contains field tags, which are numbers (1, 2, and 3). Those are the numbers that appear in the schema definition.

Field tags are like aliases for fields—they are a compact way of saying what field we're talking about, without having to spell out the field name.

Field tags and schema evolution

We said previously that schemas inevitably need to change over time. We call this schema evolution. How do Thrift and Protocol Buffers handle schema changes while keeping backward and forward compatibility?

An encoded record is just the concatenation of its encoded fields. Each field is identified by its tag number (the numbers 1, 2, 3 in the sample schemas) and annotated with a datatype (e.g., string or integer). If a field value is not set, it is simply omitted from the encoded record. From this you can see that field tags are critical to the meaning of the encoded data.

You can change the name of a field in the schema, since the encoded data never refers to field names, but you cannot change a field's tag, since that would make all existing encoded data invalid.

You can add new fields to the schema, provided that you give each field a new tag number. If old code (which doesn't know about the new tag numbers you added) tries to read data written by new code, including a new field with a tag number it doesn't recognize, it can simply ignore that field. The datatype annotation allows the parser to determine how many bytes it needs to skip. This maintains forward compatibility: old code can read records that were written by new code.

What about backward compatibility? As long as each field has a unique tag number, new code can always read old data, because the tag numbers still have the same meaning. The only detail is that if you add a new field, you cannot make it required. If you were to add a field and make it required, that check would fail if new code read data written by old code, because the old code will not have written the new field that you added. Therefore, to maintain backward compatibility, every field you add after the initial deployment of the schema must be optional or have a default value.

Removing a field is just like adding a field, with backward and forward compatibility concerns reversed. That means you can only remove a field that is optional (a required field can never be removed), and you can never use the same tag number again (because you may still have data written somewhere that includes the old tag number, and that field must be ignored by new code).

Code generation and dynamically typed languages

Thrift and Protocol Buffers rely on code generation: after a schema has been defined, you can generate code that implements this schema in a programming language of your choice. This is useful in statically typed languages such as Java, C++, or C#, because it allows efficient in-memory structures to be used for decoded data, and it allows type checking and autocompletion in IDEs when writing programs that access the data structures.

In dynamically typed programming languages such as JavaScript, Ruby, or Python, there is not much point in generating code, since there is no compile-time type checker to satisfy. Code generation is often frowned upon in these languages, since they otherwise avoid an explicit compilation step.

The Merits of Schemas

So, we can see that although textual data formats such as JSON, XML, and CSV are widespread, binary encodings based on schemas are also a viable option. They have a number of nice properties:

-

They can be much more compact than the various “binary JSON” variants, since they can omit field names from the encoded data.

-

The schema is a valuable form of documentation, and because the schema is required for decoding, you can be sure that it is up to date.

-

For users of statically typed programming languages, the ability to generate code from the schema is useful, since it enables type checking at compile time.

In summary, schema evolution allows the same kind of flexibility as schemaless/schema-on-read JSON databases provide, while also providing better guarantees about your data and better tooling.

Modes of Dataflow

At the beginning of this chapter we said that whenever you want to send some data to another process with which you don't share memory—for example, whenever you want to send data over the network or write it to a file—you need to encode it as a sequence of bytes. We then discussed a variety of different encodings for doing this.

We talked about forward and backward compatibility, which are important for evolvability (making change easy by allowing you to upgrade different parts of your system independently, and not having to change everything at once). Compatibility is a relationship between one process that encodes the data, and another process that decodes it.

That's a fairly abstract idea—there are many ways data can flow from one process to another. Who encodes the data, and who decodes it?

Dataflow Through Databases

In a database, the process that writes to the database encodes the data, and the process that reads from the database decodes it.

Backward compatibility is clearly necessary here; otherwise your future self won't be able to decode what you previously wrote.

In general, it's common for several different processes to be accessing a database at the same time. Those processes might be several different applications or services, or they may simply be several instances of the same service (running in parallel for scalability or fault tolerance). Either way, in an environment where the application is changing, it is likely that some processes accessing the database will be running newer code and some will be running older code—for example because a new version is currently being deployed in a rolling upgrade, so some instances have been updated while others haven't yet.

This means that a value in the database may be written by a newer version of the code, and subsequently read by an older version of the code that is still running. Thus, forward compatibility is also often required for databases.

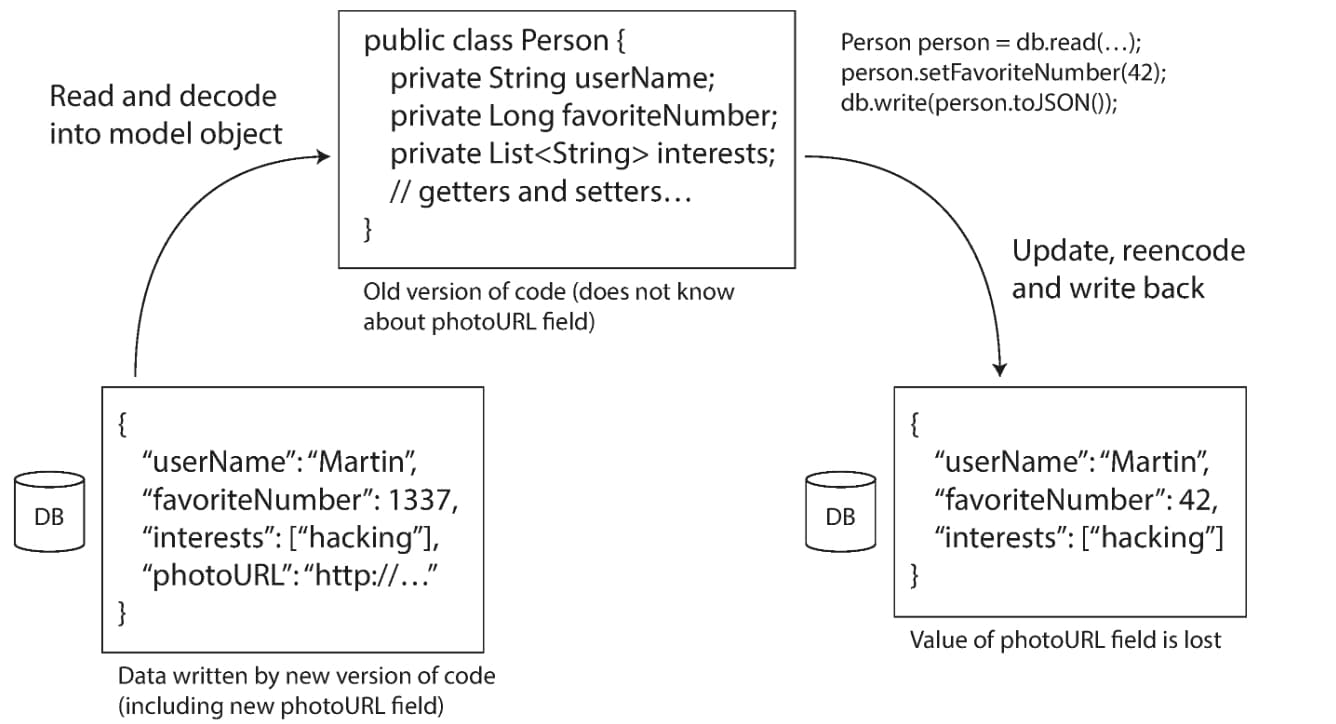

However, there is an additional snag. Say you add a field to a record schema, and the newer code writes a value for that new field to the database. Subsequently, an older version of the code (which doesn't yet know about the new field) reads the record, updates it, and writes it back. In this situation, the desirable behavior is usually for the old code to keep the new field intact, even though it couldn't be interpreted.

The encoding formats discussed previously support such preservation of unknown fields, but sometimes you need to take care at an application level. For example, if you decode a database value into model objects in the application, and later reencode those model objects, the unknown field might be lost in that translation process. Solving this is not a hard problem; you just need to be aware of it. This is illustrated in the image below.

When an older version of the application updates data previously written by a newer version of the application, data may be lost if you're not careful

When an older version of the application updates data previously written by a newer version of the application, data may be lost if you're not carefulDifferent values written at different times

When you deploy a new version of your application (of a server-side application, at least), you may entirely replace the old version with the new version within a few minutes. The same is not true of database contents: the five-year-old data will still be there, in the original encoding, unless you have explicitly rewritten it since then. This observation is sometimes summed up as data outlives code.

Dataflow Through Services: REST and RPC

When you have processes that need to communicate over a network, there are a few different ways of arranging that communication. The most common arrangement is to have two roles: clients and servers. The servers expose an API over the network, and the clients can connect to the servers to make requests to that API. The API exposed by the server is known as a service.

Moreover, a server can itself be a client to another service (for example, a typical web app server acts as client to a database). This approach is often used to decompose a large application into smaller services by area of functionality, such that one service makes a request to another when it requires some functionality or data from that other service. This way of building applications has traditionally been called a service-oriented architecture (SOA), more recently refined and rebranded as microservices architecture.

Services expose an application-specific API that only allows inputs and outputs that are predetermined by the business logic (application code) of the service. This restriction provides a degree of encapsulation: services can impose fine-grained restrictions on what clients can and cannot do.

A key design goal of a service-oriented/microservices architecture is to make the application easier to change and maintain by making services independently deployable and evolvable. For example, each service should be owned by one team, and that team should be able to release new versions of the service frequently, without having to coordinate with other teams. In other words, we should expect old and new versions of servers and clients to be running at the same time, and so the data encoding used by servers and clients must be compatible across versions of the service API—precisely what we've been talking about in this chapter.

The problems with RPCs

Web services are merely the latest incarnation of a long line of technologies for making API requests over a network, many of which received a lot of hype but have serious problems.

The remote procedure call (RPC) model tries to make a request to a remote network service look the same as calling a function or method in your programming language, within the same process.

Although RPC seems convenient at first, the approach is fundamentally flawed. A network request is very different from a local function call:

-

A local function call is predictable and either succeeds or fails, depending only on parameters that are under your control. A network request is unpredictable: the request or response may be lost due to a network problem, or the remote machine may be slow or unavailable, and such problems are entirely outside of your control. Network problems are common, so you have to anticipate them, for example by retrying a failed request.

-

A local function call either returns a result, or throws an exception, or never returns (because it goes into an infinite loop or the process crashes). A network request has another possible outcome: it may return without a result, due to a timeout. In that case, you simply don't know what happened: if you don't get a response from the remote service, you have no way of knowing whether the request got through or not.

-

If you retry a failed network request, it could happen that the requests are actually getting through, and only the responses are getting lost. In that case, retrying will cause the action to be performed multiple times, unless you build a mechanism for deduplication (idempotence) into the protocol. Local function calls don't have this problem.

-

Every time you call a local function, it normally takes about the same time to execute. A network request is much slower than a function call, and its latency is also wildly variable: at good times it may complete in less than a millisecond, but when the network is congested or the remote service is overloaded it may take many seconds to do exactly the same thing.

-

When you call a local function, you can efficiently pass it references (pointers) to objects in local memory. When you make a network request, all those parameters need to be encoded into a sequence of bytes that can be sent over the network. That's okay if the parameters are primitives like numbers or strings, but quickly becomes problematic with larger objects.

-

The client and the service may be implemented in different programming languages, so the RPC framework must translate datatypes from one language into another. This can end up ugly, since not all languages have the same types.

All of these factors mean that there's no point trying to make a remote service look too much like a local object in your programming language, because it's a fundamentally different thing. Part of the appeal of REST is that it doesn't try to hide the fact that it's a network protocol.

Summary

In this chapter we looked at several ways of turning data structures into bytes on the network or bytes on disk. We saw how the details of these encodings affect not only their efficiency, but more importantly also the architecture of applications and your options for deploying them.

In particular, many services need to support rolling upgrades, where a new version of a service is gradually deployed to a few nodes at a time, rather than deploying to all nodes simultaneously. Rolling upgrades allow new versions of a service to be released without downtime (thus encouraging frequent small releases over rare big releases) and make deployments less risky (allowing faulty releases to be detected and rolled back before they affect a large number of users). These properties are hugely beneficial for evolvability, the ease of making changes to an application.

We discussed several data encoding formats and their compatibility properties:

-

Textual formats like JSON, XML, and CSV are widespread, and their compatibility depends on how you use them. These formats are somewhat vague about datatypes, so you have to be careful with things like numbers and binary strings.

-

Binary schema-driven formats like Thrift and Protocol Buffers allow compact, efficient encoding with clearly defined forward and backward compatibility semantics. The schemas can be useful for documentation and code generation in statically typed languages. However, they have the downside that data needs to be decoded before it is human-readable.